This collection is nearing two decades old. It can register to fight in wars but cannot yet drink alcohol. Legally.

This collection is nearing two decades old. It can register to fight in wars but cannot yet drink alcohol. Legally.It's hard to debate a clinical selection of poems. The selection is based on the tastes of other anthologists, sampling a thousand, give or take, which is a good sample size. What better introduction to the genre than the best of the best retrospective?

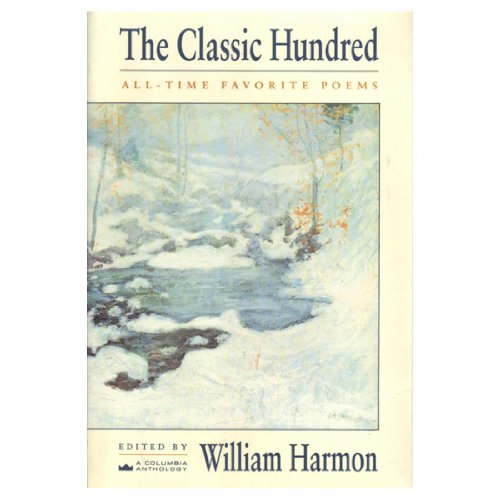

The title could mislead readers who associate "classic" with Greek or Roman culture when a more contemporary sense of the term is intended as applied to the English language.

The reader will find not only the best poems, but also a sense of the changes in subject and taste. One can also sense patterns. Some poets tend to build a laundry list of observations, then lay the reader out with a line that brings the observations into new clarity or context. Others seem to take one path, only to veer off into a new direction--the friction between the two making the poem of interest.

You'll see a number of famous stories that allude to these poems: Andrew Marvell's "World enough and time" (Joe Haldeman, Dan Simmons), "vegetable love" (Pat Murphy), "vaster than empires and more slow" (Ursula LeGuin); William Butler Yeats's "Things fall apart" (Chinua Achebe), "slouching towards Bethlehem" (Joan Didion). So you may as well check up on what some of your favorite authors have been up to.

Most surprising are some of the poets left out: Geoffrey Chaucer, Alexander Pope, and Walt Whitman. Chaucer could perhaps be explained as his greatest work, The Canterbury Tales, is read separately and not short enough for inclusion. Pope can be explained as using humor and satire, which some have difficulty equating with seriousness.

Whitman, though, is a curious case. One might point to homophobia, which might be the case for a few although most of the homoerotic aspects are subdued. Emily Dickinson shied away from Whitman as "scandalous" for an unnamed reason, which may be about what I discuss below. Even when you zoom out to the top 500, you see mostly topical (Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War). Only one seems to hint at Whitman's style or métier, "I Hear America Singing", but even that might be chalked up to illustrating the patriotism of his era as opposed to capturing the poet.

Another reason anthologists left him out might be his lack of meter and looser lines, which make him seem a lesser poet to some anthologists, especially considering the era he springs from. After all, he doesn't have much impact until Allen Ginsberg, so you'd have to wait to see Ginsberg's impact before assigning one to Whitman. The major reason for his exclusion may simply be the title of his magnum opus: "The Song of Myself," which is not especially humble. Readers today still find this mildly shocking, perhaps less so with the advent of Facebook and the Internet.

The primary downfall of the collection is that the notes are so far from the poems in the appendix. One might suggest that the reader doesn't wish to be encumbered by notes, but surely academics who are already familiar with Old English would already be familiar with these poems and probably not interested in such a collection.

It is a valuable collection to fill gaps in or rebuild your literary education. William Harmon also collected a Top 500 Poems--with even fewer notes. If you need notes, maybe grab a Norton anthology.

No comments:

Post a Comment